|

B |

eing attracted to colorful gem materials with a background story, it was only inevitable that I would fall in love with larimar soon after I purchased my first parcel of rough, during my very first visit at the Tucson gem shows in 1997. The dreamy blue exotic gem has only been on the market for about four decades, but it has captivated the hearts of lapidaries and jewelry buyers. “Loving Larimar” is the subject title I use every time I post a new piece of larimar on my Facebook page.

Larimar — even its name is lovely and poetic — is the trade name for a beautiful and rare gem, the blue variety of the mineral pectolite. Although the grayish variety of pectolite is found in various world localities, blue pectolite — larimar — is only found in the Dominican Republic, on the island of Hispaniola, in the Caribbean Sea.

The valuable blue rock is mined in a volcanic environment located five miles away from the ocean, in the mountainous southwestern region of the Dominican Republic. Small larimar boulders are occasionally washed down the hills by the Bahocuco River, and are found on the beaches near the city of Barahona, making it seem as if larimar came out of the sea. That is how it was discovered in 1974 by Norman Rilling, a member of the Peace Corps of the United States, and Miguel Mendez, a Dominican geologist. Mendez originally named the material travelina, but soon thereafter changed it to larimar, a combination of his daughter’s name Larissa and mar, Spanish for sea.

Larimar’s fame spread almost instantaneously. Armed with beautiful color, pleasing patterns, good hardness, exotic locale and history, customers the world over have embraced this gem. Since limited quantities of the material are mined every year, rough and finished goods reach only a fraction of the market, making this gem virtually unknown to a wider audience. Customers who have traveled to the Caribbean, either on a cruise ship or vacationed on the island, are probably the ones most familiar with this exotic gem. Known as piedra azul (blue stone) by the natives, the lyrical name larimar reflects the blue waters of the Caribbean and its islands, ocean breeze themes, and tropical escapes, themes that inspire customers.

Norman Rilling brought samples of larimar to the Smithsonian Institution in 1974. Soon thereafter, Dr. Joel Arem, a distinguished geologist and gemologist, visited the Dominican Republic and the mine. He was the first to publish information and photos of larimar, describing it as the “loveliest pectolite in the world” (Color Encyclopedia of Gemstones, 1977, 1st ed. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York).

Gemologist and renowned author Renée Newman included larimar in one of her latest books, the Rare Gemstones (International Jewelry Publications, 2012), and I was honored to be included with a photo of one of my favorite carved larimar brooches.

Charles Mark is the international representative of the Cooperative of Larimar Mines, and president of his very own company that sells and promotes larimar, Mountain-Mark Trading Ltd., Inc., based in Elizabeth, Colorado (http://www.larimarsource.com/). Since 1982, when Mark first visited the larimar mines, he was one of the first wholesale buyers of larimar. As a lapidary with 30 years experience, he has helped build lapidary equipment and taught the miners how to cut and polish the larimar stones. Over the years he has helped educate the public with guest exhibits and shows, and supplied specimens and information to authors.

When we first met during that 1997 trip to Tucson, Charles Mark was showing at the Howard Johnson hotel show, at Tucson’s “strip” of gem shows. He supplied me with high-grade larimar, material that I still work from today, and a friendship that has lasted for over twenty years. Nowadays, he shows at the Tucson City Center Hotel (the old InnSuites), and every year during our visit we catch up and take our ritual photo in front of his colorful banner.

The Larimar mines

The larimar mines are located near the city of Baoruco, in a mining area called Los Checheses, in Sierra Baoruco, in the province of Barahona, about 106 miles southwest from the capital Santo Domingo. The mines are accessible year-round, but the road is difficult, requiring 4-wheel drive for at least part of the journey.

Although the mineral rights belong to the government, local miners organized in a cooperative, have a 75-year lease on the mine. There are also adjacent mine sites that are independent from the cooperative. Miners use primitive tools, such as picks, shovels and hammers to break the weathered basalt, and extract the rough material. Today, miners excavate deeper and deeper into the mountainside, creating a network of tunnel mines, some of which go straight into the hill, a number of them as deep as 395 feet, while others are vertical holes. Mine huts are constructed over the shafts to protect the generators.

Over the four decades of mining, the mines have been plagued with heavy rainfall, especially during hurricane season, rock falls and landslides, and fatal accidents. Local miners brave the harsh and primitive conditions inside the mines in search of the precious material. There are continuous efforts to improve the working conditions of the mines and the safety of the miners.

Larimar’s physical properties

Chemically larimar is a hydrated sodium calcium silicate NaCa2Si3O8(OH), with copper being the cause of color. Larimar may be visually mistaken for turquoise, but it differs chemically as turquoise is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminum.

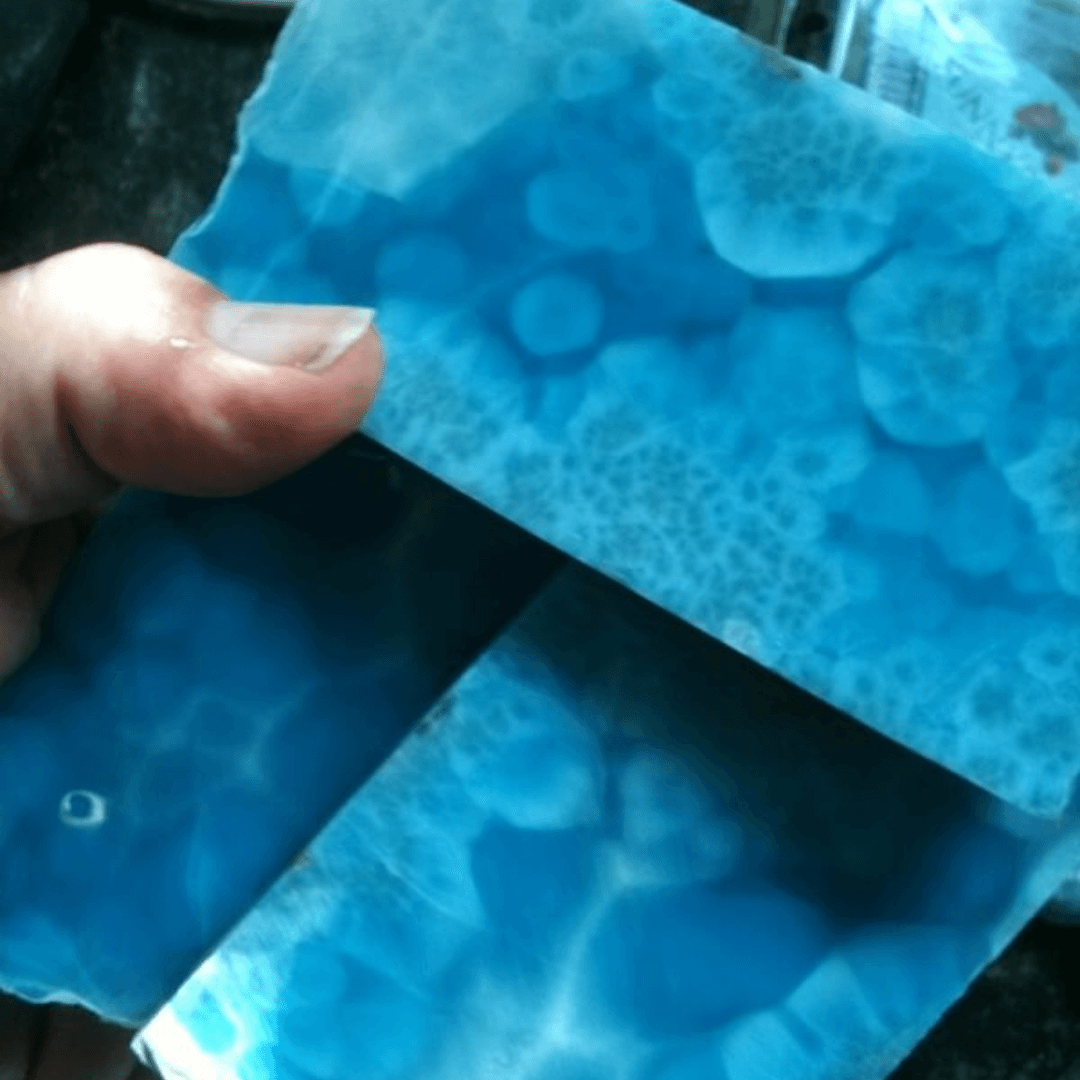

Larimar is found in shades of azure blue, turquoise blue, and blue-green, interlaced with white veins, or “white clouds”, as they are often referred to. Saturated deep blue color, intense color contrast and high translucency are attributes that bring high value to the slabs and cut gems, graded as AAA material.

The blue tones may be combined with shades of grey, brown, occasional native copper flecks and the rare occurrence of sprays, plums or dendrites (fern-like patterns) of red hematite, due to iron. All of these features may create striking “scenes” when the stone is cut. Also, fibrous, colorless calcite may fill up the center of the nodules, and inclusions of natrolite (light gray) and chalcocite (black) may occur. I am always in favor of inclusions that make the material look natural and unique, as long as there are no cracks disrupting the beauty of the stone.

The material ranges from translucent to opaque, depending on the thickness of the cabochon or carving. Larimar may often display pronounced needles and silky chatoyant areas. The rough specimens come as whole nodules, also known as “logs” or “tubes”, or as broken parts, some of them considered to be wood replacements of a tree, possibly a cycad (a tropical tree with pointed leaves like palm leaves, and cones). My personal favorites are slabs (and consequently the cabochons or carvings), that exhibit the entire radial and concentric growth pattern, even when the color is of a more pastel shade of blue.

Larimar has a refractive index (RI) of 1.599-1.628, with a typical spot RI at 1.60, and a specific gravity (SG) of 2.81. The hardness varies between Mohs 5 and 6, with darker and finely fibrous, compact material being the hardest.

Lapidary and design work

Lapidaries and designers find larimar irresistible and alluring. Traditional cabochons, freeform cabs, carvings, sculptures, eggs and spheres, are some of the forms larimar is cut into. Specimens, especially with unique inclusions, are on collectors’ wish lists. The material is also used for metaphysical purposes.

Being a material with varied composition, uneven hardness is possible across the material, a fact that often creates challenges to the lapidary. Larimar is considered a pretty tough material, however, it may have the tendency to flake or splinter, and carvers and lapidaries should be careful when working it. I have often received compliments from my fellow carvers about my carved larimar pieces, along with questions about how to overcome the flaking problem. Although I can’t say that it has not happened to me, starting with good quality rough is one suggestion. Also, avoid grinding on the lower 80 or 100-grit rough wheels. Another suggestion is to carve by moving your stone against the wheels from the outside towards to inside, away from the direction that the wheels rotate. Think of it as “folding in” the grinding, as if you were folding in dough.

The varying blue and white shades within larimar offer unlimited design style options for setting them into jewelry. I often combine larimar with faceted blue sapphires from Montana, grossular garnets, aquamarines, fire opals, pink tourmalines, as well as white and black pearls. Having set larimar both in gold and silver, it is a personal design choice, and of course, a matter of cost.

Although prices and availability have fluctuated over the years, hopefully, rough larimar will continue to reach our hands so that we can continue to create “Made in America” artwork in this beautiful, worldwide-cherished gem.

About the author

Helen Serras-Herman, a 2003 National Lapidary Hall of Fame inductee, is an acclaimed gem sculptor and gemologist with over 35 years of experience in unique gem sculpture and jewelry art. Visit her website at www.gemartcenter.com and her business Facebook page at Gem Art Center/Helen Serras-Herman.